For UX/game designers, understanding this isn’t optional — it’s essential. It’s the key to creating experiences that feel tense, emotional, and deeply human. Below, I’ve unpacked the main ideas from the video, along with examples that show how loss aversion affects design decisions, from card games to legacy mechanics to the way we frame rewards and penalties.

Designing for Emotion First

Before you design systems or stories, design feelings.

Every mechanic you include should evoke emotion — joy, tension, pride, frustration, or fear of loss. Loss aversion is one of the most direct ways to tap into those emotions.

Legacy Games and the Power of Destruction

Legacy board games use loss aversion brilliantly. They make you destroy things — cards, stickers, tokens. It feels wrong, almost taboo, and that’s exactly why it’s powerful. That act triggers an emotional response — because players are conditioned to protect their belongings. You’ve taken ownership of a card, and now the game asks you to burn it. It’s loss, dramatized.

“This was mine. I earned it. Now it’s gone.”

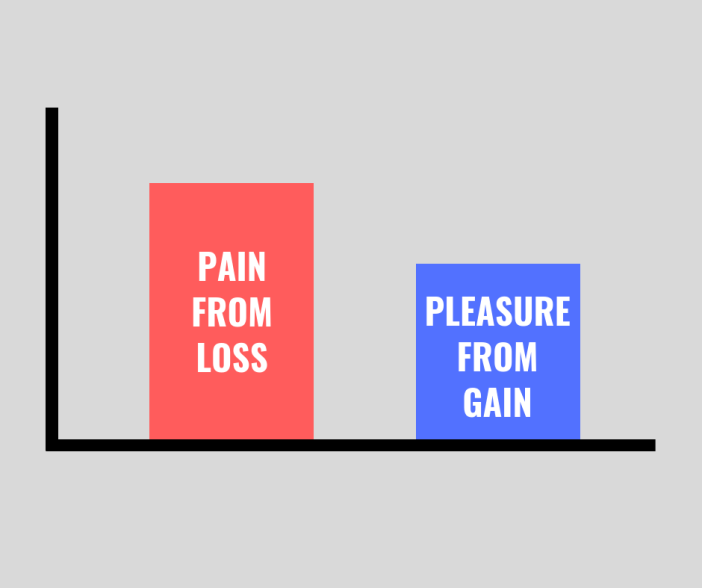

That’s the essence of loss aversion: the pain of losing outweighs the pleasure of gaining.

The Science Behind the Feeling

Example 1:

- A: Guaranteed to gain $3,000

- B: 80% chance to gain $4,000, 20% chance to gain nothing

→ 80% choose A

Example 2:

- A: Guaranteed to lose $3,000

- B: 80% chance to lose $4,000, 20% chance to lose nothing

→ 72% choose B

People prefer a sure gain over a gamble — but will gamble to avoid a loss.

That’s the psychological backbone of how we respond to risk in games.

A Card Example: Same Math, Different Feelings

“Look at the top three cards of your deck. Draw one, discard two.”

Players dislike this. They see the cards they’re losing — and it feels bad.

Now reword it:

“Look at the top three cards of your deck. Draw one. Discard two cards from the bottom of your deck without looking.”

Mechanically identical. Emotionally, far less painful. You didn’t see what you lost, so your brain lets it go. This is framing at work — same outcome, very different emotional impact.

When Loss Hurts Too Much

Old-school RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons used to include “level drain” — losing a hard-earned level. Players hated it. It felt personal and demotivating. The mechanic was eventually phased out, proving an important lesson:

Taking something away feels much worse than never giving it at all.

Deal or No Deal: The Utility of Emotion

In Deal or No Deal, the banker always offers less than the case’s expected value — yet players still take the deal. That’s because of utility, the real-life value of what’s at stake.

Winning R1,000,000 changes your life. Winning R2,000,000 doesn’t change it twice as much. The first million has far greater utility.

Players weigh emotion over math — just like in games.

Framing: The Power of Words

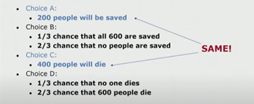

A deadly disease will kill 600 people unless action is taken.

Version 1:

- A: 200 people will be saved.

- B: 1/3 chance everyone is saved, 2/3 chance no one is saved.

→ 72% choose A.

Version 2:

- C: 400 people will die.

- D: 1/3 chance no one dies, 2/3 chance everyone dies.

→ 78% choose D.

A and C are identical — but the wording flips our risk tolerance.

In board games, the same principle applies. Instead of penalizing one player, reward the others. The math doesn’t change — but the mood of the table does.

From Losing to Building

Classic games like Monopoly and Risk are built on loss — losing money, territory, or turns.

Modern “Eurogames” flipped the formula. Games like Catan focus on growth and construction — players end with more than they started. That shift makes players feel rewarded, not punished, and keeps engagement high.

Casinos, Chips, and Illusions

Casinos are master psychologists:

- Chips make money abstract — easier to spend.

- Jackpots exploit our inability to calculate tiny probabilities.

- Chances of winning are overestimated, because losing hurts more than the numbers suggest.

The Regret Effect

In a study, players chose between keeping or switching a cup hiding money. Even when switching offered better odds, most refused.

Why? Because being wrong after switching feels worse than being wrong from the start.

Regret is powerful — it drives people to stay with the familiar, even when it’s irrational.

Competence and Control

People crave the feeling of competence — believing they understand the system.

Given two scenarios:

- You guess “even or odd,” then I roll the die.

- I roll first (hidden), then you guess.

Most choose 1, even though both have equal odds. Having all the visible information feels more comfortable — even when it’s meaningless.

The Endowment Effect

Once players own something, its value multiplies.

“This is my rifle. There are many like it, but this one is mine.”

Taking it away feels three times worse than never having it.

Designers can use this deliberately — give players something meaningful (a weapon, ally, or pet), then threaten to remove it when tension is needed.

The Endowed Progress Effect

A fascinating study by Nunes & Dreze (2006) gave customers two loyalty cards:

- 8 punches = free car wash

- 10 punches = free car wash, but with 2 already filled

Both required 8 visits — yet the second group completed the goal nearly twice as often.

People value progress they’ve already been “given.”

Settlers of Catan uses the same trick: players start with 2 victory points out of 10. That sense of “momentum” keeps players invested and striving for completion.

Takeaway

Loss aversion is the invisible hand guiding almost every emotional reaction in games. It explains why players rage over losing coins, treasure discarded cards, and take foolish risks to avoid the sting of failure.

If you understand how loss aversion works, you can design for emotion, not just logic. Because ultimately, great game design isn’t about balance or mechanics — it’s about how it feels to play.

Board Game Design Day: Board Game Design and the Psychology of Loss Aversion